Roach God: Beautifully Repulsive

Reach of the Roach God is beguiling, disgusting, ambitious, and flawed.

I backed Reach of the Roach God on Kickstarter at the physical tier.

I have three hundred and nineteen tabletop role-playing game books on the shelf immediately to my right (I counted). About half of those are some variety of hardcover; the immediate comparison I would make would be either technical manuals or university-level textbooks. While budgets have obviously increased tenfold since the early TSR days of role-playing games, the overall construction of most books hasn’t; 8.5” x 11” square-cornered casebounds, gloss finish, sales pitch art, indifferent columns of text. Even low(er)-budget zines are not immune to these design decisions, consciously or unconsciously replicating a format that remains curiously unquestioned in an industry where (nearly) every other design aspect is routinely taken apart and turned upside-down.

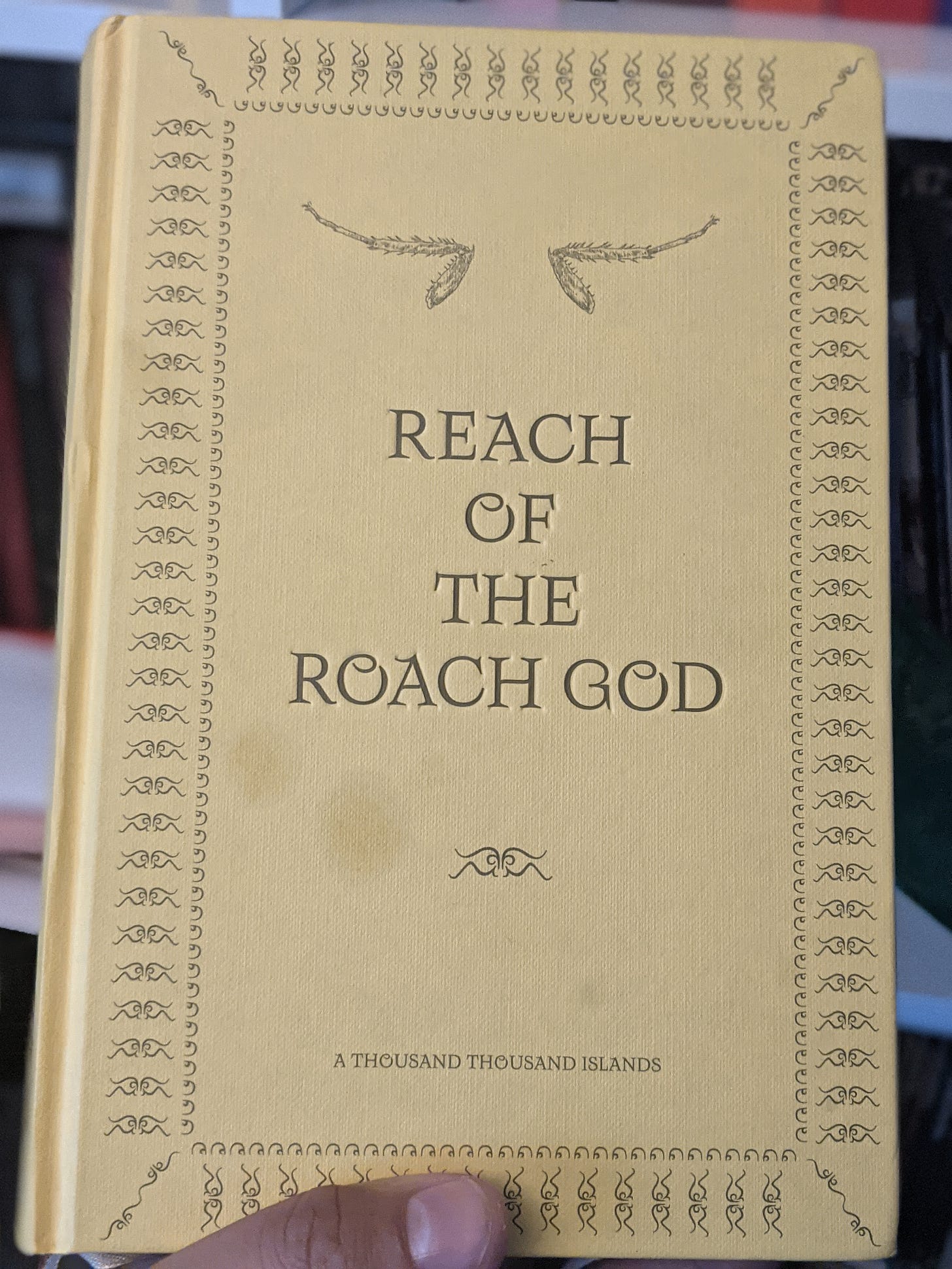

Zedeck Siew and Munkao’s concluding chapter of the A Thousand Thousand Islands project Reach of the Roach God does not conform to this archaic and somewhat awkward textbook format. Casebound, but cloth-wrapped, subtly embossed; a spine curved instead of flat to better accomodate being cradled in the hand; sewn headbands; ribbons for saving one’s page; cream-colored bookwove paper stock. This is not a book designed for shelfies or for sitting idly amongst other textbook-inspired reference texts. This is a Book in the proper sense; a novel that craves to be curled up and consumed. A tabletop role-playing game book, to be sure, but one designed to inspire play rather than presumes to dictate it.

I started to read Roach God when I got my backer PDF but held off finishing it until my hardcover arrived. It is worth the wait; this is a book I would argue that the digital edition simply does not do justice. Munkao’s art seems flat on a screen; on the page those same illustrations seem dreamlike visions, warmly settling alongside the text. There is a great deal of Munkao’s truly excellent art in this book but both in style and in substance it is entirely complimentary to Zedeck’s writing. The way art is typically presented in a role-playing game book seems almost garish and crass by comparison; as put by Sean McCoy in a Twitter thread, most tabletop role-playing game book art is designed to sell books and not necessarily supplement the text to this degree. This is archetypal of A Thousand Thousand Islands but on a much more ambitious scale than ever before.

Beyond the format of the construction of the book, the format of the construction of Roach God’s narrative is very clever. Like the vastly overrated Veins of the Earth, Roach God is a depthcrawl, luring in reader and player alike with a series of situations crafted to draw one in deeper and deeper underground following a breadcrumb trail of clues. Like Veins, Roach God follows a somewhat novel structure, presenting a choice of three settings and scenarios at the edges of the underground. Subsequent chapters outline further and deeper places one might delve and how they have become progressively and aggressively warped the closer one draws to Odoyoq itself. The titular Reach of the Roach God is both geographical, in the many waterways one follows from the surface to the depths, and metaphorical; each location to be explored and each character to be encountered has been changed, challenged, and in many cases corrupted by the spreading influence of Odoyoq.

I called this review “beautifully repulsive” for a reason and it is both one of the highest compliments I can pay to Zedeck’s prose and Munkao’s artwork and its indicative of a greater thread running through all the A Thousand Thousand Islands works. There is a base ugliness in people unflinchingly examined and unveiled, a John K. closeup on characters’ pride and lust and vice and greed and wrath the quality of which is rare to see in other tabletop role-playing game works, where the motivations and characterizations are often underdeveloped or oversimplified. There is a line in another of the Thousand Thousand Islands zines, Andjang: The Queen on Dog Mountain, which has burrowed into my brain in a way that has largely shaped my own writing: “Like the most successful tyrants, the Queen genuinely loves her country. She cares for its people. Wouldn’t you, for the animals you own?”

There is a much more literal and visceral interpretation of “repulsive” in these works as well, of course: wounds swell with pus, a monk’s head seethes with a mask of swarming roaches, muscular bodies with feet where a head should be labor in silence in the deep dark. In a private room of a temple, an apologetic spear causes anyone touched to begin to drown. Hold a flame to the chin of a dead man and collect the buttery fluid that drips out. A monk forms arrows in her mouth instead of words, spitting them fast enough to pierce steel. A mass of collected implements of murder supported by four human legs, challenging anything it sees. Anywhere else a triangular saw-jawed leech-person accountant might have been too on the nose, but Mikat can command their weight in blood and haemorrhage yours right out of your face.

Each location is exemplary of “a village with a problem”-type exposition. They are at once sprawling and intimate, dense locales of characters and places of interest tenuously connected through shared brushes with the outermost tendrils of Odoyoq. Here a mother worries for their infant, sitting upright with eyes turned black-brown, chanting nonsense*: “O DO YOQ O DO QOY”; there the master monks at a secluded temple have found a new God and shut their doors; elsewhere the caretaker of a graveyard-city trades stolen grave-goods to parasites to fund his private palace. Presented in order of complexity, I enjoyed Quiet Lake and Spider Mountain Temple as perfectly good incarnations of the typical “haunted village” and “evil temple” tropes, but it is in the City of Peace where Zedeck’s blend of the hauntingly beautiful and the unsettlingly strange really cooks. The map, in particular - a series of canopic jars and personal shrines connected by haunted tunnels - is particularly strong; Munkao is, in my estimation, an underrated tabletop cartographer, and while there is nothing wrong with the Quiet Lake or Spider Mountain Temple maps they could easily have been done by a number of worthy contemporaries. I’ve quite simply never seem something quite like the City of Peace; it is almost unfortunate that it is presented as one of three options and not the logical progression of the first section into the second.

The gazetteers in section two are a little more akin to the usual fare of A Thousand Thousand Islands; setting guides and characters strung together by theme, not plot. Bu-Ni-Ang-Ka is particularly strong writing and Blind Elephant is, if less coherent more imaginative and ambitious. This is, however, where the structure of the overall “adventure” - if we can still call it that at this point - begins to muddy. I would still call Roach God clearly superior to ideological sibling Veins of the Earth, but what Veins has over Roach God is coherence and adherence to form. Roach God part one has a clear and firm structure: three scenarios to draw characters into Odoyoq’s subterranean realm. Once there, however, Roach God seems increasingly uncertain on what exactly to do with them. The part two gazetteers would be excellent stand-alone A Thousand Thousand Island zines, but as follow-ups to the much more linear and stricter to form adventure format of part one they are frustratingly unsatisfying.

The third gazetter of part two is even less strict to form than the first two and is entirely devoted to not a place but a people: Odoyoq and their monstrous brood. It is more of a roach bestiary than anything else; I’m not entirely sure what do think of it overall. It could easily have been better presented at the front of the book, to give a better picture of Odoyoq and the roaches to prospective GMs (and the reader!) or it could have been carved up piecemeal and distributed through the other chapters as the Roach-Monarchs and their servants are encountered. To be clear: this is a very good bestiary section. It is just placed in a very awkward and somewhat nonsensical place in the book.

Chapters seven and onwards have an additional, non-roach bestiary, and a toy-drop method of determining tunnels and caves as the players journey further deepward. This part is incredibly frustrating to read and seems unfinished: it is a dungeon crawling section that is packed with the interesting minutae of dungeoncrawling but includes none of the practical aspects involved in a dungeoncrawl - time, distance, and resource management. Not to sound too much like Bryce, but the back half of Roach God seems almost unfinished: a series of compelling ideas half-strung together with fairy lights, in lieu of a statement or concrete, completed thought. If it weren’t so evocative and charming it wouldn’t work at all. As is, it serves as convenient inspiration, which for any other creative duo I might celebrate as a victory, but on the heels of the superlative first chapter and as a culmination of the Thousand Thousand Islands project I’m inclined to consider somewhat of a let-down.

The best (and worst!) thing I think I can say about Reach of the Roach God overall is that it is among the very best tabletop role-playing game books of the year, but given the time it deserves might have been among the best ever. As is, I wouldn’t even call it the very best of the A Thousand Thousand Islands works - that honor jointly and deservedly goes to Andjang: Queen on Dog Mountain and Mr-Kr-Gr: The Death-Rolled Kingdom - and might even rank Lorn Song of the Bachelor slightly higher in terms of coherence, focus, and structure in terms of adventure direction and dungeon-crawling. That said even the “weakest” of the Thousand Thousand Islands books is head, shoulders and torso above virtually every other project in the industry. Creative, communicative and financial differences have contributed to the end of A Thousand Thousand Islands as a project and that’s a shame, because Roach God could have, in my estimation, used a little more time to fester and rot.

"Hold a flame to the chin of a dead man and collect the buttery fluid that drips out." is such a good phrase... Both chilling and invigorating. This book sounds incredible.